There are those who stick to tradition and those who, without making a big fuss, seek out new flavors to impress their guests and treat themselves to a sensory experience that is different from the usual alternation between poultry and roast beef. Within this space of curiosity lies the microcosm of exotic meats: ostrich, zebra, bison, and...kangaroo, which reappear regularly on the shelves of large retailers, especially around the holidays. All of these products tell a gastronomic story that is much more multifaceted than the common imagination suggests.

This phenomenon is neither sudden nor episodic; it has deeper roots and a recent past marked by enthusiasm, media crashes, slow recoveries, and new awareness. Twenty years ago, the first exotic meats began to appear timidly in specialized butcher shops and supermarkets more attentive to new products, creating a small supply chain capable of satisfying that segment of consumers attracted by lean red meats, interesting nutritional properties, and the playful value of discovery. Over the years, a few enthusiasts continued to put their favorite cuts in their shopping carts, but then there was an abrupt halt.

The 2018 interlude and the sudden slowdown

The sector was performing reasonably well until 2018, when a media storm broke out, at least in France. As reported by 20Minutes, the association 30 Millions d'Amis, amplified by the activism of comedian Rémi Gaillard, denounced the sale of exotic meats during the festive season. Within hours, the issue ignited social media, generating reputational pressure that forced many brands to withdraw the products, even though they were legal. This polarization has left scars: the companies involved speak of plummeting sales, communication shock, and a climate of generalized suspicion.

Nicolas Papin, director of Maison Papin, explains this clearly in the French newspaper: “The issue of animal welfare has become one of the major concerns for consumers, and sales have fallen dramatically since then, although we have seen a recovery in the last two or three years.” This case shows how public opinion can influence smaller sectors more drastically than food giants, which do not have the same media protection.

What buyers are looking for

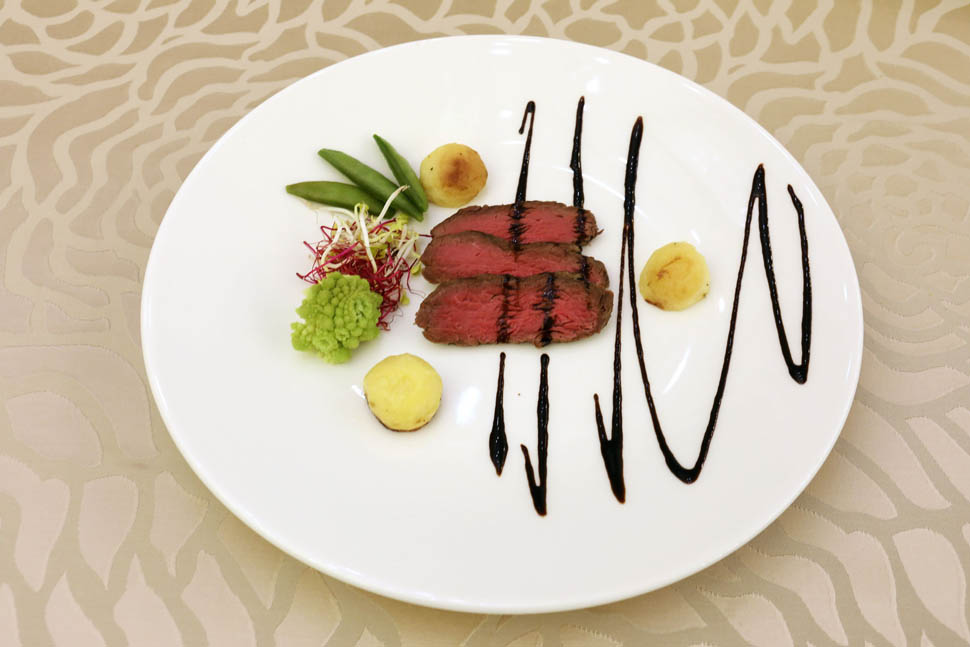

Those who decide to serve these meats—especially during the holidays, as they are often very expensive products—are not only motivated by the desire to impress. There is a trend towards lean red meat with high protein content, low fat content, and a distinctive flavor profile. Ostrich, for example, is more like filet mignon than chicken; bison is appreciated for its intensity and soft texture; kangaroo has iron notes and a strong character; zebra, when it was marketed, had a texture similar to that of European game. If you want to find some examples of restaurants serving kangaroo in Italy, there is no shortage of them: in Abano Terme (Padua), the 5-star Hotel Terme Tritone offers sliced kangaroo fillet with balsamic vinegar topping, extolling the properties of this low-fat, protein-rich cut.

Il Tempio della Carne in Turin, on the other hand, writes on its website: "This product comes from animals raised in the open air, which means they have the right muscle tone to cope best with grilling and pan-frying. The flavor is certainly exotic, but when enjoyed rare, a slice of kangaroo meat is a real treat for the palate because, unlike other rare selections, it remains tender and is easy to eat, making it very enjoyable." If of excellent quality, it could be a worthy competitor to Chianina beef. There is also a link between these choices and the contemporary trend to consume less meat, but of higher quality, investing in the individual experience rather than turning it into a routine. Returning to France, Papin emphasizes this: “There are customers who want to change their habits and treat themselves to a different pleasure, in the same way as those who choose Wagyu or Black Angus.” Despite the curiosity, the commercial calendar is strict: it is a seasonal market, with a time frame concentrated almost exclusively in December.

How the supply chain really works

The collective imagination tends to mix Sub-Saharan Africa, savannahs, poachers, and Western cuisine. A cinematic narrative that does not correspond to real protocols, at least according to those who work in the sector. Damien de Jong, head of the company of the same name near Strasbourg specializing in game and exotic meat, explains it clearly: “We only import authorized meat that has undergone very strict controls.” For years, his company has been selling cuts such as kangaroo or bison pavé, ostrich strips, and even some species that are now banned, such as llama and zebra, when they were still permitted. The crucial point concerns the status of the animals in their countries of origin. In Australia, kangaroos are considered a species to be controlled, just like wild boars in many regions of Italy. In South Africa, ostriches and other ungulates are part of legal supply chains, certified and managed with hunting quotas. Perception changes because the cultural context changes. Papin sums it up as follows: “For us, the kangaroo is a victim to be protected, while in Australia it is a problem to be managed, and hunting quotas are assigned each year to prevent overpopulation.” The window of gastronomic understanding often involves emotional and symbolic factors rather than technical criteria.

The ethical dilemma

Exotic meats, more than others, bring with them a moral and symbolic debate. Is it acceptable to eat a European deer but not a South African zebra? Which animals fall into the “acceptable” category and which into the “unacceptable” category? As always in gastronomy, there is no universal answer: it varies according to culture, education, personal memory, and the amount of storytelling that accompanies a dish. The same logic explains why horse meat is eaten in some regions of Italy and taboo in others, or why octopus arouses empathy in some diners and enthusiasm in others. In addition to the symbolic dimension, there is the issue of hunting sustainability and animal welfare. The European supply chain requires veterinary checks, traceability, and certification, and hunting in the areas where kangaroos and ostriches come from is regulated by quotas that are renewed every year, with ecological impact assessments.

The sector repeats this insistently, because transparency is a fundamental currency today. In his more experimental years, De Jong even tried to introduce camel, crocodile, and moose. It was a time when variety was pursued as a gastronomic value. Today, however, many species are banned for human consumption in Europe, and the range has narrowed. “It is no longer possible to import certain species, and the market does not favor diversification,” he admits. However, curiosity has not waned: those who appreciate these meats are not looking for quantity but experience, just as is the case with certain raw milk cheeses, single-origin chocolates, or bottles of terroir spirits.