In 2017, when Ikoyi opened its doors, Chan knew he was challenging the system. He rejected “laboratory” tests, taste tests, and repeatable recipes. Each dish came to life for the first time in front of the customer. Each dish was a risk. Vulnerability. Improvised art, calibrated to the millimeter.

Cover photo: Danny J. Peace

Portraits in the article: ©Maureen M. Evans

The chef

He has never tasted a single one of his creations. Not out of eccentricity or arrogance. Jeremy Chan cooks like he writes a visceral poem. Every dish that comes out of the kitchens of Ikoyi—the London restaurant that climbed the world rankings in 2025, winning the Highest Climber award in the World's 50 Best Restaurants list—is a fragment of his autobiography. And how do you eat a piece of your own soul? “It would be like devouring myself,” he says in an interview with the well-known international network.

Born from a vision that rejects labels and embraces the unknown, Ikoyi is not an African, Asian, or French restaurant. It is an independent territory without borders, where spices are language and memory, and flavor becomes an emotional archive. It is a place where cooking, more than expression, is expulsion: the transformation of interiority into edible matter. According to Chan, taste is not just a matter of the palate. It is a multidimensional, layered experience that intertwines matter with the moment, aroma with nostalgia, texture with context. But eating something in an alley in Hong Kong, on a flight after a farewell, or in the controlled silence of a Michelin-starred restaurant is never just nourishment: it is a psychic and physical journey, an act that absorbs and restores who we are.

“Flavor is the result of our current state, of our experiences. We cannot cage it in definitions.” This awareness guides Chan in every culinary gesture and has led him to reject any preconceived “concept.” Ikoyi was born in a fertile void, ready to be invaded by any detail of life: a Nigerian pepper soup, a Cantonese broth, the rarefied elegance of a white truffle on a Parisian veal chop. “Flavor is the output of my life's journey,” he states resolutely. Those who cross the threshold of Ikoyi enter a sort of alchemical ritual. In this kitchen, spice is not a decorative element, but the key to a burning and sacred emotional world. It is pain and pleasure together, joy and memory condensed into a burst of aromatic fire. “I wanted to use spice as a creative catalyst,” says Chan, “because it is through the fire of spices that my imagination takes shape.” In 2017, when Ikoyi opened its doors, Chan knew he was challenging the system. He rejected laboratory tests, taste tests, and repeatable recipes. Each dish comes to life for the first time in front of the customer. Every dish is a risk. Vulnerability. Improvised art, calibrated to the millimeter, like an orchestra playing live without a score, but with such deep cohesion that it seems to be remote-controlled by the heart.

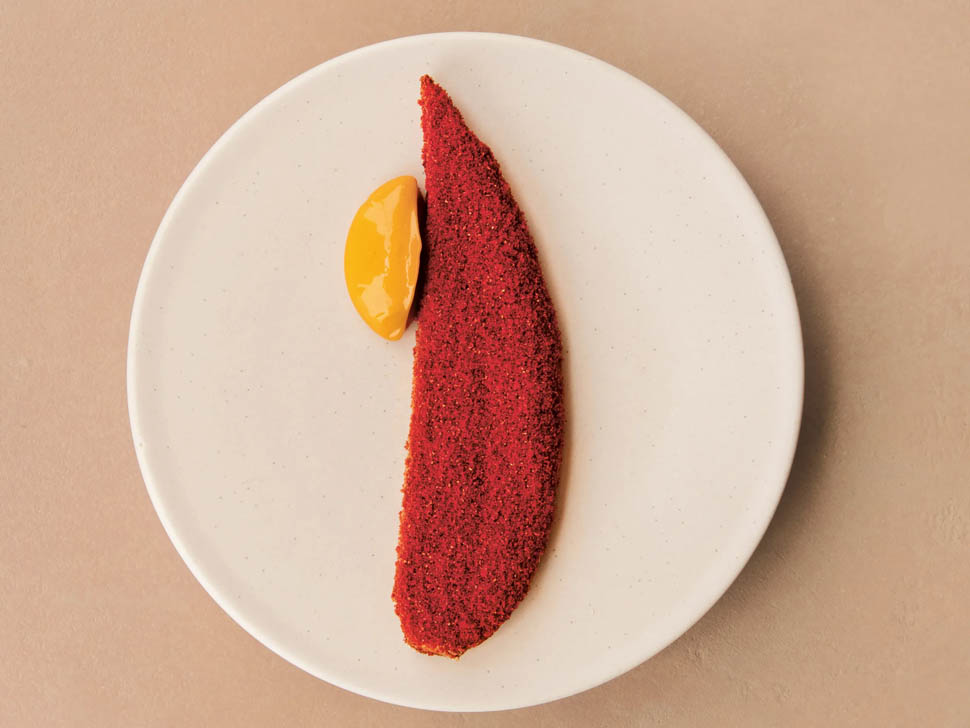

It's not jazz, it's not blind freedom. It's extreme rigor. It's sharp minimalism that compresses years, memories, spices, and pain into a single bite. A zucchini flower immersed in an intense reduction. A cuttlefish chopped up and slowly cooked that explodes in your mouth with the cry of the sea. It is a cuisine that aims to look like it was created by a machine, but thrives on the most human of frailties: unpredictability. Chan's most unsettling statement remains this: he has never eaten in his restaurant. He has never put a fork in one of his dishes. He doesn't want to. He doesn't have to. Because his cuisine is not meant for him, but for others. “The reason I cook is to see the joy in the eyes of those who eat, not to experience what I have created.” An idea that seems crazy in an age of obsession with control, but one that embodies a deeply spiritual vision. For Chan, cooking is like a football game played without tricks, without widening the goalposts to make it easier to score. Or like a symphony orchestra that refuses to be recorded, relying only on the here and now, with all the fragility and power of real sound.

Every ingredient that enters Ikoyi has a story. The beef, for example, changes every day: size, color, marbling, texture. “I can't control how the animal lived, but I can listen to what it tells me,” explains Chan. And so each steak is treated differently, observed and read like a different poem. The dish is born from this relationship, from this silent exchange between man and nature. The philosophy is clear: you cannot create authentic food unless you use ingredients that carry the same integrity. The product is an extension of its past, and the cuisine is the amplified echo of all the lives involved. From the hands of those who grow it, to the seasons, to the soil. It is a symphony of existences. Chan also rejects the fashion for “purity” at all costs: the naked ingredient, the unseasoned oyster, the ‘perfect’ strawberry served as it is. “It's a form of exclusion,” he says, “a refusal to be contaminated, to let in other flavors, other consciousnesses.” On the contrary, his purity is syncretic: it comes from mixing, from embracing everything he has encountered and loved. A minimalism that does not simplify, but layers. In a single bite, it leaves you with the echo of ten places, twenty sensations, thirty years of life.

Time, however, is not always an ally. The more time passes, the more outside voices creep in. Customers, trends, awards. “When we opened, I didn't care what other people thought. But now I listen too much, and that pollutes the purity of ideas,” he confesses. It is the risk every artist faces: giving in to the idea of pleasing everyone and losing oneself. But Ikoyi remains a shining light in the night. A cuisine that comes from within and offers itself to the world, even at the cost of not being understood. Even at the cost of burning a little. Because true flavor is not only in the mouth, but in that secret place where memory merges with the skin. And where every dish, if done well, can tell you something you didn't know you knew.