How a talented chef from Puglia earned a Michelin star in the Swiss Alps, bringing recognition to the peaks of Verbier at 1,500 meters above sea level.

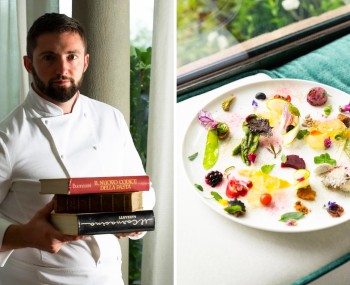

The chef

Among the snow-capped peaks of Verbier, where the air smells of pine resin and the sunsets look like watercolors, there is a place where time stands still and cuisine becomes poetry: the Chalet d'Adrien, a sumptuous five-star residence nestled in the Swiss Alps. But more than the magazine-worthy comforts—29 cozy rooms, a Clarins spa, a panoramic pool—it is Sebastiano Lombardi's touch that makes this gastronomic oasis a pilgrimage for gourmets. At the helm of the “Table d'Adrien,” the only Michelin-starred restaurant in Verbier, the Apulian chef has brought with him the scent of the sea and the tenacity of the mountains, blending tradition and creativity with an almost musical rigor. On the other hand, Lombardi has significant experience in Italy, to which he is deeply attached (just think of his leadership at Il Cielo, the restaurant at Relais La Sommità in Ostuni, and Il Pellicano in Porto Ercole after Antonio Guida), but he chose the Swiss mountains years ago.

Originally from the sunny countryside of Puglia, in Andria to begin exact, Sebastiano Lombardi grew up with his feet in the earth and his mind among the aromas of his grandmother's cooking. And it is precisely there that his culinary “madeleine de Proust” lies: acquasale, a poor dish but rich in memories, consisting of stale bread, cold water, anchovies, onions, celery, tomatoes, and oregano. “It used to be the reward after a day in the fields,” he told Food&Sens magazine, “a cold, invigorating soup, sometimes enriched with a little fish.” A hymn to simplicity, where every ingredient speaks of the land, hard work, and affection.

If he were to be a vegetable, Sebastiano would choose green beans: humble, versatile, discreet, but capable of surprising bursts of flavor in the kitchen. When it comes to wine, a good glass of Champagne, which for the Italian chef is the drink of special occasions, but also of small daily celebrations. In his pantry, among spices and aromas, one of his favorite flavors is Vadouvan, a French blend with Indian influences that finds its perfect match in Lombardy cuisine. It's a bold combination, like any successful encounter between cultures and latitudes.

Among his favorite dishes, riso, patate e cozze (rice, potatoes, and mussels) shines brightly, symbolizing Bari cuisine. It is a dish that speaks the language of popular cuisine, where rice intertwines with potatoes in a salty embrace with mussels, creating a gratin dense with memories and feelings. There is no nostalgia, however, in Lombardi's cuisine: if anything, there is a respectful rewriting, which starts from the roots but knows how to soar to new heights. Not everything, however, finds its way into his kitchens. One deliberate omission is eel. “I love it, but it's an endangered species, and I prefer to give it up out of respect for the sea and its balance,” he explains firmly. This gesture is consistent with a broader philosophy, which is also reflected in his daily fight against plastic. “It's not easy in a professional kitchen, but it's a necessary battle. I prefer to work with local suppliers: the Entremont and La Magne farms supply us with cheese, eggs, vegetables... The important thing is that they can guarantee both quality and quantity.”

Every day, the chef repeats a simple but powerful mantra to his team: “Never give up.” This phrase encapsulates his entire vision of the profession: consistency as the key to success, dedication as the driving force, perseverance as the compass. “Talent alone is not enough in the kitchen; you need discipline, a spirit of sacrifice, and a desire to always improve,” he says. It is a prudent vision, but one imbued with humanity and passion. His sensory universe is composed of opera notes sung by Pavarotti and the scent of freshly cut grass in the fields. A symphony of images and smells that are reflected in his dishes, always constructed with an almost obsessive attention to consistency and consistency. Nothing is left to chance, nothing is left to improvisation.

Two figures have illuminated his career: Antonio Guida, two Michelin stars at the Mandarin Oriental in Milan, and Nino di Costanzo, chef at Daní Maison in Ischia. He shared an intense journey with both of them, one of rigor and poetry, technique and vision. Yet the dream that remains unfulfilled is perhaps the most tender: to let his family, who still live in Puglia and have never tasted his Michelin-starred dishes, try his cuisine. It is a desire tinged with melancholy that speaks louder than a thousand words about the heart of a chef who, despite his lofty position, has never forgotten his roots.