Over 50 years of success for a family-run restaurant that focuses on delicious dishes from Italy, with a few detours: fried brains and lamb's head, ravioli, soups, and frog legs are all part of Paolo's repertoire in Madrid.

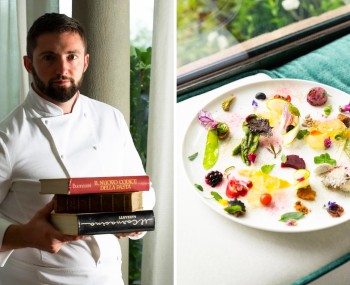

Portrait on the cover by Álvaro García

The restaurant

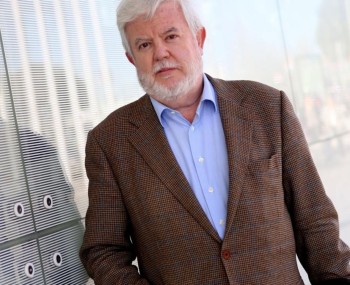

There are places that stand the test of time, not by trying to stop it, but with the grace of those who welcome it and preserve it like a rare treasure. Paolo, a trattoria hidden away in Madrid's Islas Filipinas neighborhood, is one such place. Opened in 1972, when Italian cuisine was still a novelty and the area was considered the suburbs, this restaurant has gone through five decades without giving in to the temptation of plastic modernity. Today, as then, those who cross the threshold find themselves catapulted into another era: carpeted floors, wooden walls, and well-set tables that look like they came out of a 1970s photo shoot. There is something deeply reassuring about this unchanging space, almost as if memories have taken shape among the chairs and wall lights. It is no coincidence that the outdoor pergola that welcomes customers is part of a residential building dating back to 1969 — a detail that Miguel Revuelta, the current owner and son of the founder, likes to recall with a touch of pride.

“My father thought it would last five years. A passing fad,” he told El País in this beautiful interview by Abramo Rivera. The fad has passed, but Paolo has remained. Not only that, he has become a small institution, known for his home-style cooking, unpretentious but with attention to detail, and for his declared love of offal, which is treated here with respect and patience. At the helm of the kitchen is Álvaro, Miguel's brother, who has been carrying on the family philosophy for over thirty years with traditional dishes and small touches of innovation. The menu has been streamlined compared to the exuberant years—when up to four carts full of appetizers, cheeses, compotes, and desserts were paraded around during each service—but it has retained its soul intact.

The pasta section is a journey in itself: each dish survives only if loved by customers. The carbonara, for example, costs €12 and follows the classic recipe with just one deviation: pancetta instead of guanciale. The ravioli are assembled strictly by hand, with fillings that change with the seasons—currently gorgonzola and spinach—while the spinach lasagna is made with homemade dough rolled out by hand. Surprisingly, there is also a dish that would seem out of place, but which has become an icon here: smoked salmon pizza, thin and crispy, requested by the most loyal customers. Among the most emblematic dishes are the hake cheeks in green sauce, perfect in their gelatinous consistency, the baccalà al pil-pil (salt cod with garlic and chili pepper) and the oxtail stewed in red wine, one of those dishes that seem to cradle the stomach and the soul. And then, of course, there are the offal dishes: pork trotters cooked in small quantities, breaded lamb brains on request, and pork cheek stewed in white wine. The menu also includes some lighter but no less tasty offerings, such as fava beans with ham and egg, vegetable soups, and pochas, a traditional Iberian legume. Everything is prepared using fresh ingredients and with genuine respect for the ingredients themselves.

The menu also includes some vintage touches, such as the shrimp cocktail with pink sauce (€13), served in a glass as tradition dictates, or the Roquefort endives (€10), evidence of a retro taste that has won over even the youngest palates. The spacious and welcoming dining room is enriched by a collection of authentic antiques collected by Miguel over the years: 19th-century bullfighting posters, rare engravings of famous bullfighters, and above all the splendid lamps from the Sicilia-Molinero tea room, which operated in the 1930s on Gran Vía and were designed by architect Luis Gutiérrez Soto. All are original pieces, carefully chosen to avoid kitsch and instead tell a story. And if the eye is satisfied, the palate is not to be outdone. Paolo also has a little gem for cocktail enthusiasts: their Dry Martini, considered one of the best in Madrid. Served in a smaller than usual glass and chilled to perfection, it hides a secret: a dash of MG gin from the 1950s, which gives the drink a touch of the past.

Finally, to complete the picture, there is an extraordinary wine cellar, enriched by fortuitous but wise purchases: bottles from the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, from private collections and sold at more than reasonable prices. “Not for speculation, but for drinking,” says Miguel, proudly showing us a 2004 Viña Albina or a 1996 Viña Real, also available for $35. Paolo is not just a restaurant: it is a fragment of shared memory, a time capsule that smells of slow-roasted meats, handmade ravioli, and antique wood. It is a place where time does not run, but walks slowly and decisively, like an elegant waiter bringing a plate of history to the table.