Although the winery now has a thousand references, the project continues to be managed by just one person. “I am the chef, the sommelier, the community manager... I am Bisavis,” explains the owner.

The format

An Excel spreadsheet instead of a wine list is not a provocation, but a statement of method. Eduard Ros hands it to customers at his restaurant Bisavis with naturalness, as if it were the most obvious thing in the world, and observes their reactions: amazement, a few smiles, then confident acceptance. Seven hundred lines, hundreds of references, an enological atlas that rejects the reassuring form of a list ordered by appellations and prices. That seemingly unsettling gesture encapsulates the identity of a restaurateur who changed his life, language, and perspective based on a simple yet radical awareness: knowing that he does not know. “I learn about wine every day, and after learning so much, I still feel like I know nothing; and that's what excites me,” says Ros in a recent interview with La Vanguardia. The Socratic quote that opens his story is not a cultured quirk, but the pivot around which a project built outside the canonical paths revolves. A lawyer by training, he spent ten years in law before making a sharp turn toward gastronomy and wine, which he approached without prestigious schools or official mentors, but with fierce discipline and a curiosity that has never ceased to bite.

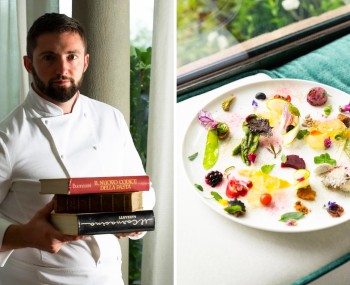

Bisavis started out almost seven years ago as a restaurant, with an initial selection of around fifty labels. However, wine quickly took over, forcing Ros to move premises in order to accommodate a cellar that now boasts almost a thousand references. Despite the larger space, the structure remains minimalist, almost monastic, because the project continues to be run by a single person. “I am the chef, the sommelier, the community manager... I am Bisavis,” he explains. The secret? For Ros, wine is neither a complement nor an ornament. It is the reason why many people cross the threshold of the restaurant. “I think many came to see a good wine list and then stayed for the wine and food.” The order of the words matters. Wine comes first, not out of snobbery, but out of deep conviction: "In 99.9% of pairings, wine is at the service of food. I don't like this idea. Nothing should be at the service of anything else." It's a stance that shifts the focus of the gastronomic discourse and is reflected in the behavior of the public. According to Ros, today half of the customers who walk into Bisavis are thinking mainly about what to drink, not what to eat.

This focus is also reflected in the way the wine cellar is presented. No glossy menus, no seductive descriptions. Just a spreadsheet, destined to change over time. The selection is not based on fashion or market criteria, but on a very personal notion of commitment. "These are wines that I might not take home today, but which have been important to me. Wines made by serious people, made with care, that tell the story of a territory and its people.“ Over time, tastes have changed radically. ”I fell in love with the world of wine through wines that I wouldn't drink today." This is not an admission of inconsistency, but of growth. For Ros, a good wine list doesn't have to appeal to everyone, it has to be readable. He is not worried about confusing customers. On the contrary, it becomes part of the experience. “When you hand them an Excel spreadsheet with 700 lines, they are surprised at first, then they relax and start talking. They tell you what they want to drink, you listen to them and guide them.” The relationship of trust starts right there, with dialogue. “More and more people trust my judgment, and that makes me happy. My reputation is based more on the wines I drink than on what I earn.” Behind this vision, however, there is also a critical reflection on the language of wine and the role of professionals. Ros does not mince words: "We are partly to blame. For years, we have used difficult language, which has created barriers. Sometimes it is a form of protectionism." He adds an important detail: for him, sommeliers do not only work in restaurants. They can be distributors, producers, or sellers. Anyone who knows how to open bottles and conversations.

The topic of pairings is also approached with caution. Ros does not like rigid formulas, but he does not shy away from pointing out some key points. Chocolate with a high cocoa content remains a difficult territory for him, especially with dry wines, while he recognizes happy affinities between scallops and full-bodied Albariño, or between caviar and Champagne, thanks to the combination of acidity, creaminess, and salinity. When asked to break another dogma, that of red wine with meat, he replies without hesitation: for a matured beef tartare, he would choose a biologically aged white wine from the Jura, capable of supporting structure and complexity. The discussion then broadens to the relationship between restaurateurs and high-priced wines. Ros observes a widespread contradiction: people are happy to buy expensive perishable products, but hesitate when faced with bottles costing over forty euros. For him, the difference is simple: good wine does not expire and adds value to the restaurant, even if not everyone will choose it.

Bisavis ultimately appears to be the natural extension of a mind that rejects definitive certainties. A place where wine ceases to be an object to be displayed and returns to being a living practice, made up of study, mistakes, and listening. In a landscape often dominated by simplifications and narrative shortcuts, Eduard Ros chooses the longest and most fragile path: that of permanent curiosity.