Here, food is not designed, it is experienced. The team works like a family that has learned respect through hands-on experience, not rules. And feeding is a moral verb even before it is a gastronomic one.

The place and the philosophy

There is a point, on the hills that rise lazily from the plain and climb towards the Apennines, where the road stops running and begins to breathe. A sharp bend leads to Poggio, a farmhouse where life is lived with the land and not against it. Here there are no Instagram-worthy forests, nor posters promising immersive experiences. There is real land, hard work, and an agricultural rhythm that does not bow to fashion. There is a sincerity that does not ask permission or seek applause, because the truth, in the countryside, does not need an audience.

It is cultivated as it was once cultivated: bent backs, waiting, silences that fill more than words. The wines are natural, even too much so. Untamed. Spontaneous, volatile, acetic fermentations, long macerations, bottles that seem like characters in a rustic drama: intense, irregular, free to the point of excess. Sometimes it feels like living in Waiting for Godot: you look at them, you listen to them, and you're not sure when they'll come to fruition. Maybe tomorrow, maybe never, maybe right now if you take them without wanting to understand them at all costs. These are wines that don't come to you. If anything, they wait for you, and they decide whether it's worth opening up.

The beauty—or the nightmare, depending on who you are—is that they do nothing to soften themselves. No makeup, no consoling sweetness. They have that sincere turbidity that scares those who drink labels more than wine. Here, you look at the glass and immediately understand if you are in the right place: if you want surgical cleanliness, you can go elsewhere. If you want life, even when it stings, take a seat.

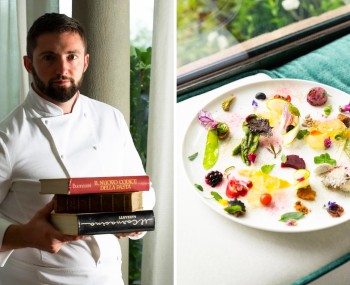

The kitchen

The kitchen follows the same instinct: here, food is not designed, it is experienced. The team works like a family that has learned respect through hands-on experience, not rules. They really enjoy themselves: they tease each other, laugh, knead dough. They sing Christmas carols even in August, with the heat coming out of the oven and flour suspended in the air like snow that refuses to melt. And as they hum Tu scendi dalle stelle, the rolling pin beats on the table, the dough stretches, the kitchen vibrates. It's not folklore: it's a hard-won serenity, built on trust and complicity.

And then there is fresh pasta. Tortelli are a throwback to times gone by: the herbs for the filling are still chopped by hand, one by one. There are no cutters, no anonymous factory-made paste; there is fiber, moisture, and the true fragrance of vegetables. It is extremely rare, almost an act of cultural stubbornness. It's a way of saying: we're not in a hurry, it's you who are rushing. Anolini, on the other hand, are close relatives of wine: rough, intense, sometimes gruff. They have a vein of pungent flavor that doesn't ask permission and comes straight to the point, like an affectionate slap from a peasant grandmother. It's cuisine that doesn't court you, it challenges you — and then embraces you when you understand the language.

The appetizers are a small agricultural manifesto. Lots of vegetables, never ornamental: bitter leaves, wild herbs, vegetables treated as protagonists, not side dishes. Not the fake nature of the restaurant that roasts a zucchini and calls it countryside: here the vegetables taste of chlorophyll, sap, resin, sun. A lively, stimulating complexity that makes you think of the field, the season, the air. A sensory exercise that does not seek to impress: it wants to remind you where food comes from.

And then there is the seasonal omelet. Small, humble, almost shy at first glance. But it is a ritual. Each season brings its own: in spring it is tender green with nettles and peas; in summer it smells of zucchini, basil, and wildflowers; in autumn it is loaded with pumpkin, onion, and rosemary; in winter it huddles in the earth, with black cabbage and frost-resistant herbs. It is a gesture of peasant cuisine that says more than a thousand words: this is what there is, this is what the earth gives. No staging, just truth on the plate. You can order à la carte, of course, but the tasting menu is almost a secret shared among those who know how to listen — and it costs very little compared to what it tells. It is more of an agricultural ritual than a menu: a complete narrative of short supply chains, daily work, and awareness. No luxury, no pretense: just completeness. Every ingredient has a face, a field, a reason. And you can really feel it.

On the subject of cured meats, allow me to add a personal note: they are delicious, authentic, and made with care. But with such high standards and such authenticity on the plate, perhaps there is room for even more in-depth research, a further push. A leap that would bring them to the same dizzying level as the pasta and vegetables. I say this with affection, not arrogance: everything here flies high, and it would be nice to see the cured meats reach the same heights. There are moments, between one dish and another, when the kitchen door opens and you hear a bit of dialect, laughter, the sound of pans. A pot bubbles, someone shakes out the tablecloth, a dog dozes on the threshold, waiting for something to fall. The romance is not sought after, it is inevitable. Bread is bread, not an aesthetic interpretation: a crust that sounds hollow, a crumb that holds. The broth smells of real bones and patience, the meat does not melt on its own — it needs a knife and determination. And all this is not meant to impress: it is meant to nourish. And nourishing, here, is a moral verb even before it is a gastronomic one.

Then summer arrives. The cicadas start singing before dinner, the light bites and caresses, and tables are set up on the terrace outside. Iron creaks, tablecloths flutter in the wind, glasses sparkle like little sun lamps. And if you happen to find yourself sitting next to a group of extremely friendly Romans, you risk ending up in an Ozpetek film: Le fate ignoranti (The Ignorant Fairies), but with handmade tortelli and a refermented wine in your glass. Hearty laughter, sudden confidences, broad and happy humanity. It cannot be constructed: it just happens.

And when you leave, don't do it right away. Walk towards the vineyard. The sun is setting, the golden hour transforms everything into a warm bath of gold and silence. The air enters your skin, puts you back together. You don't look at your phone, you don't search for words. You are here. Whole. Alive. And as the light slowly settles on the leaves and the earth, you thank God that places like this still exist—and that you happened to pass through today, at the very hour when the world stops demanding and simply lets itself be seen. When you leave, with the sun reddening the hills and the breeze carrying the scent of hay, you feel something different about you. Not the glossy lightness of magazine-worthy places, but the solidity of an agricultural gesture that needs no justification or embellishment. A place where wine doesn't wear its Sunday best, and the cuisine doesn't put on lipstick. Where everything is alive, imperfect, and therefore necessary. In a world that smooths, here it scratches. And you thank God that it does.

Contacts

Località Poggio Superiore di Statto 6, 29020 Travo PC

Phone 334 154 4810

andreacervini.ilpoggio@gmail.com