There are restaurants that tell the story of a cuisine. And then there are places like Ombre Mosse, which tell the story of a worldview. Not a hyper-technological and reassuring future, but an oblique, lateral present, where time bends and form becomes thought. Entering it means crossing a fissure: Parma remains outside, with its elegant and orderly tradition; inside, a mental space opens up that vibrates like a painting by Mattioli—surfaces that are only apparently immobile, traversed by an internal tension, “voladora,” by shadows that never stand still.

The environment is minimalist and essential. It is a conscious, meditative subtraction. The lighting is measured, the volumes clean, the shadows structural. Nothing distracts: everything converges on the gesture, the dish, the idea. It feels like being inside a pictorial setting from the 1970s, both metaphysical and concrete, where every detail is necessary and nothing is decoration. But Ombre Mosse is not just a place: it is an imaginary TV series, a series that was never filmed, set between 1972 and 1976, with slightly dusty colors, a hypnotic rhythm, and a psychedelic soundtrack pulsing in the background. And like any great series, it has its characters.

The cast: organized madness

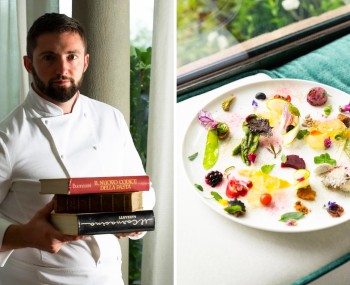

Holding everything together—vision, cuisine, dining room, philosophy—is Pierluigi Gorgoni, the true orchestrator of the project. A central, magnetic figure, intoxicated with genius and a fertile, creative, necessary madness. Pierluigi does not direct: he convenes. He is the invisible director, the one who pulls the strings without ever tightening them, who allows chaos to exist but only to the extent that it generates meaning. His is a feverish mind, capable of holding together rigor and momentum, discipline and delirium. Ombre Mosse is his open score: each service a variation, each menu a rewriting.

In the kitchen, Ilian Emili, Francesco Scamardella, and Michel Adjassou, very young chefs who seem to have stepped out of the 1970s, not in terms of aesthetics but in terms of attitude, are at work. Their movements reveal quiet concentration, seriousness without rigidity, and disciplined freedom. Cooking as an ethical act rather than a gastronomic one. Cooking as a stance, without proclamations. Precise, physical, anti-rhetorical gestures. Chefs who build the invisible depth of a menu: stocks, extractions, fermentations, slow preparations.

In the dining room, Sebastiano Ambrosoni, an alchemical creator of symphonic kombuchas, moves about. He does not accompany the dishes: he interprets them. His fermentations are narrative instruments, veritable liquid scores. Each pairing is a musical bar that enters at the right moment, clarifying, amplifying, shifting the axis of taste. It is he who translates Pierluigi's lucid madness into liquid.

Vegetables as a political gesture

Ombre Mosse's philosophy is clear and practiced without compromise: raw, unadulterated sustainability. Here, circularity is not a buzzword, but a fundamental structure. Nothing is wasted. Not even bones, which are turned into consommé of an almost ascetic purity. Not even peels, stems, or parts considered minor. But above all, something even rarer happens here: vegetables cease to be an alternative and become sovereign. Roots, leaves, tubers, and vegetable fermentations are neither side dishes nor stylistic exercises. They are the center of the discourse. Meat, when present, accepts a feudal role: vassal, sometimes valvassore. It brings depth and memory, but it does not dominate. In an era in which vegetables are often used as an ideological banner or as technical virtuosity, Ombre Mosse restores them to their original political dimension: feeding without wasting, working over time, accepting bitterness, digging beneath the surface. Eating roots today is a radical gesture. It means choosing depth over brilliance.

The menu: a narrative in acts

Prelude

Carrot butter is a primary revelation. The extracted carotene colors the butter an almost psychedelic orange. Fat and vegetables blend together; Maldon salt arrives like a bright fracture. The fir and venison focaccia (or with kimchi in the vegetarian version) is a manifesto. The fir in the dough brings resin, winter, forest. The venison sauce, made from trimmings and offal, is dark, deep, controlled. Here, sustainability becomes an intensification of flavor. Radicchio in oil — Treviso, Lungo di Milano, Variegato di Chioggia — is peasant memory brought to surgical precision. Elegant, persistent bitterness. The cold infusion of pine and lichen closes the prelude like a mental walk in an imagined forest.

First act - freshness and crunchiness

The venison carpaccio, vermouth, and sage is essential and sharp. Raina's vermouth brings oxidative notes, while the sage oil adds fragrance without being overpowering. In the vegetable version, the variegated turnip does not imitate: it offers another language, with the same tension. Radishes, daikon, and beetroot play on sweet and sour and smokiness. The beetroot under ash is pure earth; the stems in sour marinade provide rhythm. Sweet spices layer. The kombu gin and tonic is a side note: iodine, cleanliness, verticality.

Intermezzo - velvet

The egg white, truffle, and herb pudding, chawanmushi style, suspends time. Discreet truffle, deep mushroom soy, wild herbs as green accents that exorcise palatal boredom. A meditative dish.

Second act

The egg yolk agnolotti, venison neck and licorice are restrained power. The licorice comes through at the end, like a long note. The ingannapreti with shallots and licorice demonstrate that the emotional structure of the dish does not depend on meat.

Interlude

The consommé—goose or vegetable with green tea—is the ethical heart of the menu. Clear, deep, necessary. Here you really feel that nothing is wasted.

From the à la carte menu — a necessary detour

It is precisely between the interlude and the third act, in this space of suspension that Ombre Mosse grants the diner, that one of the most revealing moments of the entire lunch arrives. A detour from the main score that is by no means a distraction, but a technical solo of the highest level: guinea fowl in three courses. A dish that, more than any other, lays bare the profound expertise of the kitchen. Because if there is one meat that is unforgiving, that easily betrays the chef's hand, it is guinea fowl. A noble but ungrateful animal, often destined to become dry, stringy, and monotonous. Here, however, the opposite is true. The first course is a crostino with giblet sauce and fir oil. A concentrated, dark, deep bite that works on the memory. The giblets are never iron-like or exhibitionist, but bound together, harmonized, almost sweetened by the fir oil that brings resin, cold air, verticality. It is a beginning that prepares the palate, makes it attentive.

Next comes the roasted thigh with lovage. Here, the technique begins to speak softly but with extreme clarity. The meat is juicy, relaxed, cooked in a way that respects the fibers. The lovage does not flavor: it guides. It recalls celery, greenery, and vegetal depth, creating an invisible bridge with the rest of the menu. The third course is the real test: roasted breast with grilled clementines, accompanied by a carrot sauce made from concentrated juice and a touch of black lemon. Here, the chef's skill is measured. The breast, a part that is by definition prone to dryness, remains incredibly juicy, tender, and alive. There is no trace of thermal stress, no fibers that close up. The carrot sauce adds natural sweetness, the clementines bring a burnt freshness, and the black lemon adds an oxidative, almost ferrous note that lengthens the sip and the bite.

This dish does not seek immediate applause, but slowly wins you over, demonstrating mature, quiet technical mastery without ostentation. It is a lesson in cooking, in respect for the ingredients, and in absolute control of heat. Paired with Malbec Kunf Fu Riccitelli, it is a surprisingly apt choice: dark fruit, energy, a tension that accompanies without overpowering, supporting the meat without stiffening it. A wine that is not the protagonist, but the accomplice. This guinea fowl is not an afterthought. It is a statement. Here, technique is not virtuosity: it is care.

Third act

The 30-day dry-aged venison grilled over charcoal dialogues with a Mexican-inspired mole negro, surprisingly similar to the Tuscan dolceforte. The lactic-fermented fava bean pods bring lively acidity. The grilled Lungo di Milano radicchio, with sour honey and rosehip, is pure balance. The scorzonera, glazed with truffle and Blu del Monviso, is one of the most intelligent and profound vegetable dishes I have tasted this year. The mille-feuille of roots and leaves, with fermented blueberry sauce, layers earth, acidity, and green with surgical precision. Sebastiano's coffee kombucha closes the circle with a dark and very lucid vibration.

Finale

The pre-dessert of cabbage and buttermilk toffee—two ingredients, no salt, no sugar—is a purely political act. The postlude with dried figs, pumpkin seeds, ficu cheese, and hibiscus infusion is adult sweetness, not seductive.

Conclusion

Ombre Mosse does not seek consensus. It demands attention. It is a gastronomic and cultural journey that is absolutely worth the experience. And in a time of crazy prices, those tasting menus at $45 and $60 are a radical gesture. Here, sustainability is not marketing. It is structure. It is organized madness. It is a shadow that moves.

Contacts

Ombre Mosse

Borgo Giacomo Tommasini, 18, 43121 Parma PR

Phone: 351 488 0775