It's the Christmas calling card of Michelin-starred chefs: from Bottura & Tiri to Gennaro Esposito, from Oldani to Romito, from Cracco to Cannavacciuolo: all the signature baked goods that make Christmas so special.

There is a moment every year when the kitchens of Michelin-starred restaurants stop talking only about tasting menus and start thinking in terms of kilos, paper molds, and linen cloths. It is the moment when panettone goes into the oven—and with it, regions, family memories, collaborations with fashion, dreams of travel, even tickets to climb the Milan Cathedral. Because today, panettone is no longer just a Christmas dessert: it is a chef's second calling card. It is the promise that the fine dining experience, usually confined to a restaurant, can be recreated in its entirety at home, amid the sound of knives sinking into the cake and the “just give me a thin slice” requests that we already know how they will end.

On this tour of Italy's finest leavened products, Michelin stars serve as our compass. From three-star chefs who ship panettone as if they were small luxury treasure chests, to young one-star chefs who work with sourdough with artisan determination, to those who have changed the very idea of panettone forever—such as Gualtiero Marchesi—and those who have brought it into fashion boutiques. It is a sentimental map, even more than a gastronomic one. We will try to trace it, following the scent of butter and citrus fruits coming from the kitchens of great chefs.

Three-star chefs: panettone as an extension of the restaurant

Niko Romito: the essence of dessert

In Niko Romito's world, panettone is almost a monastic exercise: a large leavened cake “cleansed” of all frills, leaving only structure, aroma, and digestibility. From the Niko Romito Laboratory, in collaboration with the PANE project in Castel di Sangro, comes a traditional 1 kg panettone that is the perfect translation of his gastronomic philosophy: three days of preparation, three progressive leavening processes, live sourdough starter, selected flours, fresh cream butter, candied orange peel, citrus honey, almonds, and Bourbon vanilla. It looks like a classic panettone, but one sniff is enough to understand that behind it lies the same research that Romito applies to broths, vegetables, and bread. Alongside it, the pandoro created to support the Veronesi Foundation and the pandolce—a tall brioche available in several variations—expand the family of leavened products, but the heart remains that panettone, which is only “neutral” in appearance, perfectly calibrated, which tells the story of Abruzzo, the daily work of the laboratory, and his own idea that luxury today is lightness.

Massimo Bottura, Gucci Osteria, and Tiri's dough

In Florence, panettone literally enters boutiques. At Gucci Osteria, Massimo Bottura entrusts Vincenzo Tiri, one of Italy's most beloved bakers, with the dough for a strawberry and chocolate panettone, soft, long-lasting in the mouth, dressed in packaging that speaks the language of the fashion house. Alongside it is a more “bourgeois” traditional version, but still based on patient leavening and ingredients calibrated to the millimeter. It is the most explicit encounter between haute cuisine, fashion, and fine pastry: panettone as an object of desire, but also as a story of the supply chain—from Tiri's workshop in Basilicata to the Gucci-branded boxes.

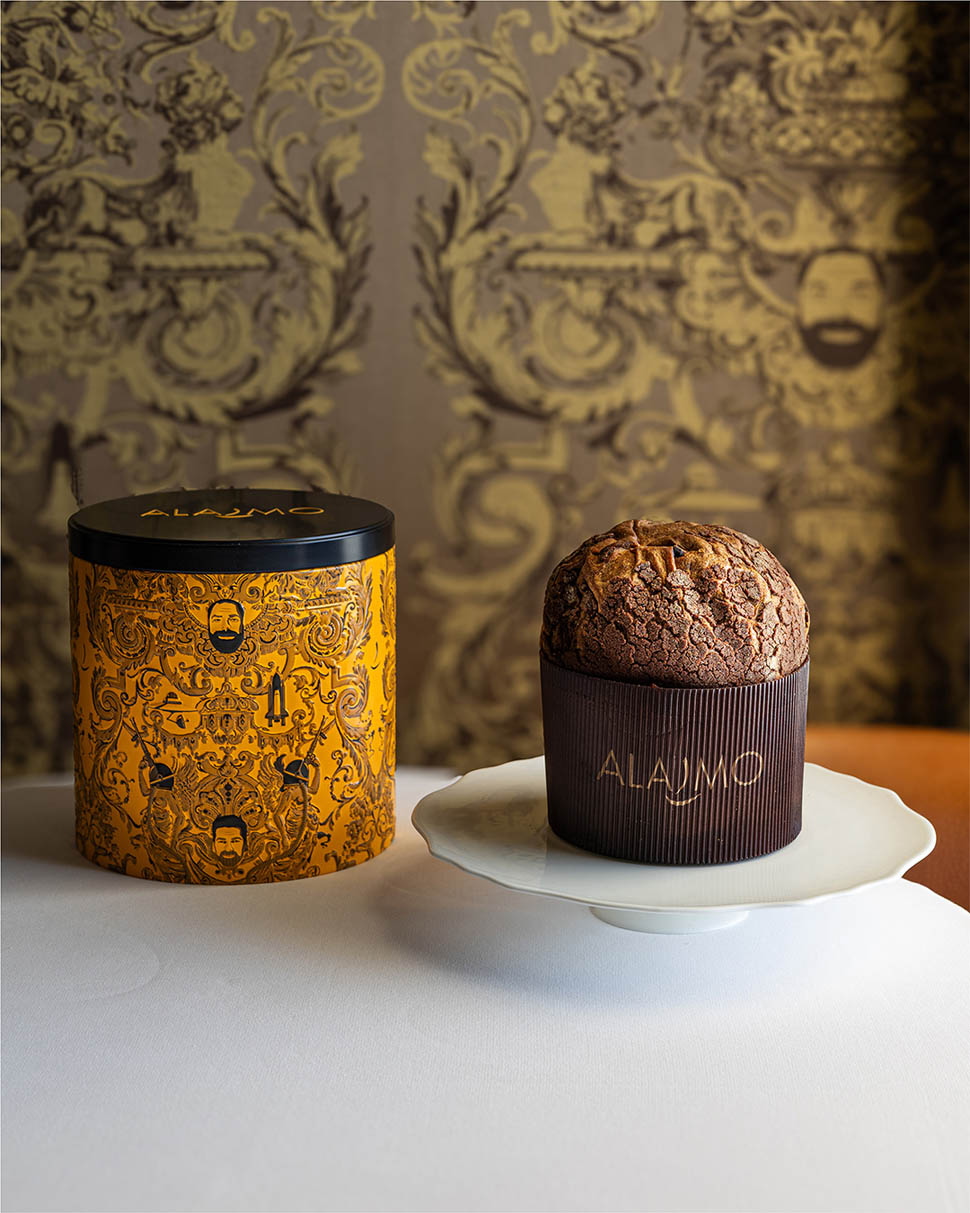

Alajmo: the collection that plays with Christmas

At Alajmo, panettone is not a seasonal product: it is part of the family lexicon, a way of telling the story of the group through doughs that change their appearance every year but not their identity. Massimiliano is in charge, of course, but the grammar of sourdough is in the hands of executive pastry chef Alessandro Pesavento, who orchestrates a veritable collection: the Arlecchino, a classic with extra virgin olive oil, candied orange and citron, light and reassuring, almost a “subtractive” panettone that plays on the purity of its aromas; the Moro di Venezia, chocolate and marasca cherries with a sac-à-poche of cream to squeeze on top, designed as a dessert to finish at home, in a somewhat childish and very playful gesture; the Ducale, a richer interpretation, with gianduia and dark chocolate, a limited edition that looks like a jewel; Mediterraneo, with lemons, capers, olives, and candied chili peppers, which brings the idea of a “savory journey” typical of their cuisine to the world of leavened products; and Olimpico – Cortina 2026, with candied apple and orange, walnuts, and cinnamon, designed as the official panettone of the Winter Games: a dough that smells of snow and chalets, but remains deeply Venetian in the way it balances sweetness and spice. Pesavento works on the technical details, while Alajmo keeps his eye on the bigger picture.

Uliassi: 350 panettone cakes as a numbered series

In Senigallia, Mauro Uliassi brings his obsession with the sea and the local area to a limited edition panettone: around 350 pieces, made in over thirty hours, with double leavening and a supply chain that speaks Marche – local flours, selected honey, artisanal candied fruit – and a strong Mediterranean touch, such as Corrado Assenza's bergamot. The workshop of his friend Francesco Pompetti, supervised by Alessandro Brigatti and pastry chef Rosita Mammone, works like a small perfume factory. It is not a product for the shelves: it is almost an invitation into their close circle, a dinner at Uliassi that lasts until New Year's Eve.

Perbellini. When panettone is a family affair

Giancarlo Perbellini has created a “family” panettone, developed in collaboration with his children Ilaria, Alessandro, and Andrea, and his cousins Pierluigi and Laura at the historic Pasticceria Perbellini in Bovolone. There are two main versions: classic with orange peel, citron, and raisins; and chocolate with different percentages of cocoa nibs, for a play of bitter and sweet. It is a panettone that carries the weight—and lightness—of a decades-long confectionery tradition.

Cannavacciuolo: Vesuvius in the oven

At the three-star Villa Crespi, Antonino Cannavacciuolo has transformed panettone into a collection. The Suno laboratory, led by pastry chef Kabir Godi, produces the great classics—Milan, almond, gianduia, limoncello, Annurca apple—but also variations that seem like little travel stories: pear, cinnamon, and ginger; whole wheat with chocolate and red fruits; the “Vesuvio Red Velvet,” red, spectacular, just the right amount of tart, studded with white chocolate chips and cranberries. There are also 500-gram versions, a vegan option, and even a savory pizza-style leavened cake, which brings Campania to Lake Orta in the form of pizza disguised as panettone. Here, the leavened cake becomes a manifesto of a cuisine that loves the extra, the generosity, the “more” that makes you say enough but makes you take another slice.

I Cerea: the apricot that smells of Collio

For the Cerea family in Brusaporto, Christmas tastes like Panettone Albicocca e Collio Picolit: a great classic that started out as a limited edition and has become a recognizable signature of the “Da Vittorio Selection.” Alongside it are Milano and Cioccolato: butter, honey, vanilla, and candied fruit treated with the same care that the Cerea brothers reserve for fish prepared to perfection. Here, panettone is not a gadget: it is the natural extension of a home bakery that over the years has become a brand, with dedicated shops, workshops, and distribution that remains thoughtful and non-invasive.

The noble father: Gualtiero Marchesi and the idea of the “right” panettone

Before chefs' panettone became a phenomenon, Gualtiero Marchesi had already put his signature on a recipe. In 1986, he imagined the “perfect” panettone: not too tall, without excesses, with a triple and very slow leavening process that aims for perfect consistency rather than visual effect. Today, 1,500 numbered Panettone Gualtiero Marchesi cakes are produced and sold by the Foundation: the same idea of simplicity, the freshest ingredients, no preservatives and a shelf life of at least forty days, with a balance of butter, candied fruit and air pockets that rejects extremism. The proceeds finance the Foundation's cultural projects. It is an almost educational panettone, reminding everyone—chefs included—that the essentials, if done well, need no tricks.

Northern Italy: between design, memory, and precision. Milan, capital of signature leavened products

Panettone is at home in Milan, but chefs are rewriting the recipe. The result is a chorus of different voices, where panettone is never “just” a dessert, but a piece of the restaurant's identity.

- Carlo Cracco offers a small collection: from the Classic Milan to caramel and pistachio versions, three chocolates, and “Delizie” with spreadable cream, enclosed in illustrated tins reminiscent of his Galleria. It is a panettone that thinks like a dish: layers of textures, carefully studied combinations, price, and packaging that immediately declare the category in which it plays.

- Davide Oldani takes his “pop cuisine” one step further and literally turns it into a postcard of Milan. His D'Om de Milan panettone, in collaboration with the Fabbrica del Duomo, arrives at your home with two tickets included to visit the monumental complex and climb up to the terraces. A gift within a gift that transforms a slice of cake into an excuse to see Milan from above and, at the same time, contribute to the preservation of its most iconic symbol. The cake becomes a key to the city, a gastronomic and cultural experience in a single box.

- With Andrea Aprea, two stars in Milan, there are two types of panettone: traditional with candied fruit, or with Vesuvius apricots. The packaging made from recycled coffee paper conveys an aesthetic sustainability even before environmental sustainability, consistent with the idea of contemporary and conscious cuisine.

- Aimo e Nadia, Etro, and panettone as a fashion item. Il Luogo di Aimo e Nadia, with Alessandro Negrini and Fabio Pisani, works on two levels: on the one hand, the Aimo e Nadia Artisanal Panettone, a classic Milanese recipe made with live sourdough, long rising, and aromas of citrus and vanilla; on the other, the collaboration with Etro, which dresses a saffron and milk chocolate panettone in a decorated tin, almost like a collector's bag. Tradition and fashion intertwine: the dough remains authentic and “serious,” while the container plays with desire, with the pleasure of giving and receiving an object that is not just for eating.

- Andrea Berton remains on the side of rigor. His panettone—Sicilian orange peel, Diamante citron, Australian raisins, Bourbon vanilla—seems to reflect his cuisine: measure, precision, an almost obsessive choice of raw materials.

Horto, IYO, Griffa, Chieppa, Vergine: new trajectories in the North

- Also in Milan, Horto (one star and Green Star) transforms panettone into an almost artisanal project: 350 numbered pieces, packaged in natural fabric bags hand-embroidered by the Apulian workshop Oriens. The leavened cake becomes an object to be treasured, a unique piece that speaks of time, hands, and looms.

- At IYO, pastry chef Kim Kyunjoon brings the Far East to the dough: yuzu and halabong, Jeju citrus fruits candied in Korea using artisanal techniques, tonka beans, and milk chocolate. The panettone is served to guests at the end of the meal and sold online: a soft bridge between Milan and Asia, where candied fruit is no longer just orange but an atlas of flavors.

- The line moves further northwest with Paolo Griffa at Caffè Nazionale in Aosta, who creates a classic hazelnut and almond glazed panettone, inspired by childhood memories and that childish gesture of stealing almonds from Turin's glazed pastries.

- On the Ligurian coast, chef Jacopo Chieppa (Equilibrio, Michelin star) dedicates his panettone collection to Liguria: from the classic version with raisins macerated in Pigato wine to the “Coccola” with extra virgin olive oil, candied olives, white chocolate, and lemon, to the Savona chinotto and creative gianduia versions.

- In Brianza, Matteo Vergine with his Grow works on a 100% natural panettone, sourdough, without preservatives, in only 300 units: classic or chocolate and apricot, it reflects a young cuisine, also supported by the recognition of Best Young Michelin Chef 2025.

Piedmont: Vivalda and Del Cambio

In Piedmont, panettone speaks both the language of the Langhe and that of historic cafés.

- At Antica Corona Reale, Gian Piero Vivalda has created AtelieReale, a dedicated workshop where Panettone Reale and its variations are made: long-rise dough, stone-ground flour, Piedmont IGP hazelnuts, Moscato d'Asti, Piedmontese butter. The idea is to reinterpret a great classic with the same meticulous care that Vivalda reserves for his menu items.

- In Turin, the Ristorante Del Cambio entrusts the Farmacia Del Cambio with the task of telling the story of Christmas: the low, glazed panettone, an icon of the restaurant, is recalibrated every year. In 2025, the recipe features candied orange selected by Corrado Assenza, inside a soft, golden dough in which raisins and citrus zest retain a recognizable aroma. The packaging draws on the Pharmacy's 19th-century history, while the laboratory also creates a new limited edition pandoro.

Central Italy: sea, embers, and memories

Between the Adriatic Sea and the hills of the Marche region, panettone becomes a tale of fire and salty wind.

- We have already met Mauro Uliassi, with his panettone made from Marche grains and targeted collaborations. In Loreto, at Andreina, Errico Recanati brings the embers directly into the dough: butter smoked with a mixture of seven woods—the same ones that fuel the fire in the kitchen every day—and homemade candied fruit give life to a panettone that tastes of smoke, roasts, and good ash. It is a dessert that does not simply “celebrate Christmas,” but recounts the memory of the embers of Andreina's home.

- In Friuli, Emanuele Scarello with Agli Amici 1887 creates a panettone with apricots macerated in Picolit, honey, butter, and vanilla: a leavened cake that is almost like a wine to eat, the perfect symbol of a cuisine that brings together the Friuli countryside and an international flair.

It is central Italy that is not afraid to get its hands dirty with smoke and wine, to open up panettone to the dialect of its own territory.

South, Coast, Sicily: Pellecchiella apricots and the sea in the alveoli

If there is one region that has turned panettone into a choral novel, it is Campania.

The Vesuvian constellation

- At the Torre del Saracino in Vico Equense, Gennaro Esposito has been working for years with AMPI master Carmine Di Donna on a family of panettone that starts with the classic Milanese version and expands to include chocolate, black cherry, orange, apricot, apple, grape, and cinnamon versions. It is a continuous interplay between the coastal climate and Milanese tradition, where Di Donna's technique meets Esposito's Mediterranean sensibility.

- At Taverna Estia (two Michelin stars), Francesco Sposito creates a Vesuvian Panettone with “pellecchielle” apricots, a symbol of the area, with 36 hours of leavening and a dough that tastes of sunshine and citrus fruits.

- In Sorrento, on the terrace of the Grand Hotel Excelsior Vittoria, Antonino Montefusco has created a panettone that reflects the elegance of his restaurant, Terrazza Bosquet: Vesuvio apricots in the classic dough and an orange-dark chocolate variation, available in one-kilogram and half-kilogram sizes for those who just want to “try” it but then regret it.

- Peppe Guida, with the Antica Osteria Nonna Rosa, makes panettone in his workshop with his son Francesco: a few pieces, handmade, in flavors ranging from classic to melannurca, apricot, black cherry, coffee, and chocolate. The tone is that of home cooking elevated to a system: no special effects, just a freshness that speaks of a warm oven and family.

- On the Amalfi coast, at the Furore Grand Hotel, executive chef Vincenzo Russo presents Bluh Christmas: three versions—classic, almond, and apricot—that transform panettone into a concentrated journey through the flavors of Campania, from raisins to candied orange to dried fruit.

- In Milan but with a Neapolitan soul, Roberto Di Pinto and his Sine offer “O' Panettone”: classic lemon and saffron, as well as limited editions with triple chocolate and hazelnut, matcha, and pistachio. The dough is made in Sal De Riso's laboratories on the coast, as stated on the label: a transparent bridge between two southern brands.

Sicily and beyond

In Sicily, Ciccio Sultano puts his name on panettone cakes that resemble little baroque tales: the traditional “Sicilia,” the limited edition Re Moro, and the chocolate version. All made with sourdough, without preservatives, with the same care for the raw ingredients as in his preserves and Turiddu pasta kits. Here, the panettone smells of citrus fruits, almonds, cocoa, but above all of that idea of joyful abundance that Sultano's cuisine brings to the table at ORA in Ragusa Ibla.

ALL OF ITALY IN THE "ALVEOLATURA"

Seen from a distance, these panettone cakes all look the same: dark paper, browned domes, ribbons, and boxes. But as soon as we sink our knife in, Italy opens up in cross-section: the Langhe and Collio, Vesuvius and the Amalfi Coast, the wood-smoked hills of the Marche, the sea of Senigallia, the fog of Milan, the Baroque stones of Ragusa. Each chef, each brigade, each workshop has chosen a detail to tell its story: a citrus fruit, a sweet wine, a glaze, a collaboration with a fashion house, a ticket to climb the Duomo, a hand-woven bag. And panettone, a family dessert, has become a new language of haute cuisine: democratic because it arrives on the family table, radical because it allows no shortcuts.Perhaps this is its charm: a great leavened product is a matter of time, daily care, and repeated gestures. It is the least spectacular part of a chef's work, the part that does not end up in a 15-second reel. But it is precisely there, in the hours of waiting between one refreshment and another, that you understand how much a Michelin star knows—or does not know—how to transform itself into domestic warmth. So yes: this year, even before booking a table, we can choose a panettone and take home a piece of all these stories. The slice will be soft, fragrant, more or less creative. But if the baker has really put their mind, hands, and heart into it, the sound of the knife sinking in will be enough to remind us why we will never stop wanting another slice.